“Never was a cornflake girl. Thought it was a good solution, hanging with the raisin girls.”

Tori Amos, Cornflake Girl

In order to understand Gen X, you have to understand ‘90’s grunge. It’s kind of our calling card. We’re the “apathetic” generation, the “in-between” generation. The gap between our under-controlled boomer parents and our over-controlled millennial and Gen Z children. We had an analog childhood but a digital adulthood. We were not the digital natives that followed; nor the digital immigrants of our elders.

The enemies of our parents were neutralized. The Berlin Wall fell down. Reagan visited Gorbachov. George Bush, Sr. defeated Sadam Hussien. Everything seemed just peachy. No need to get fired up about anything. The middle-class thrived and everywhere you looked teenagers were inventing new technology, and fresh rock’n’roll, in their garages and dorm rooms.

Ours was not an apathy of not caring, it was an apathy of “someone else will take care of it.” A confidence in life to figure itself out. We were latch-key kids after the wave of stay-at-home mothers no who longer stayed at home, but before the latch-key kids grew up and realized they didn’t want their seven-year-olds sitting at home unsupervised. The antics I got up to in my neighborhood in Northern California are things I would never allow for my own children. But, then, at the same time, we all say, “It was fine for us.” We survived. Why can’t we have that same lackadaisical attitude about our own children? Instead, we entered the uber-safety-helicopter-parenting that prevented the exact exploration needed for things like Dell and Facebook. And grunge.

Grunge was not about death or despair or “failing mental health.” It was more about the angst of growing up, communicated in chords. It was about accepting that the world used to suck, might suck again, but here we are in the middle just trying to live one day at a time. Death wasn’t feared or celebrated; it was honored. Suicide was respected with awe; it was never an actual option. We all considered Kurt Cobain a brave martyr when he shot himself. In April, 1994, he became a rock god. An idol, icon of bucking the system and not letting “The Man” control him. This nebulous thing: The Man - the Boss, the CEO, the establishment, the authoritative entity that would suck our lives away day by day - was the real enemy. Not Russia. Kurt Cobain had shown them. He wasn’t going to be enslaved.

We watched as our parents and grandparents spent decades of their lives chained to a job they hated only to retire on a pittance pension and drink themselves to death. We watched as our parents and grandparents married young and either lived miserably with a partner they loathed or got divorced and moved on to another failed marriage.

I entered adolescence prepared to stick it to the man. We weren’t going to lie down and become enslaved to the ivory tower. We were gonna fight for our right to party. We weren’t gonna take it.

I’m not sure what the ‘it’ was that we weren’t going to take. Maybe it was the conventions of our predecessors. Maybe it was just life itself.

In eighth grade, the biggest strike against my social acceptability was that my parents were still together. By then, I had so many strikes against my social status that I had lost count somewhere in fourth grade. Today we would call it “bullying.” I can’t do that - give them power, make myself the victim - when we were all no more and no less than kids trying to survive a cruel world. The girls who treated me badly were only doing what they could so they weren’t treated badly. We all felt like shit inside. Some people just reacted to it better than others. Some girls decided to make everyone else feel as shitty on the outside as they felt on the inside.

In eighth grade, I didn’t wear make-up. I hadn’t tried alcohol, or kissed a boy. I still read “children’s” books: Little House in the Prairie and Anne of Green Gables. I hadn’t even grown breasts or started my period, though I pretended. I stuffed my bra in junior high school gym; joked about that “time of the month.”

I began ninth grade the day after my parents announced their divorce, and entered school the next day in a daze. Everything in my world had been flipped upside-down and turned inside-out.

All I could think about was whether this would be a boon or a bomb for my peer status.

When my dad came out of the closet, though, I knew the answer. Perhaps in 2024 this would propel me to the top of the fourteen-year-old social ladder. In 1993, it was a popularity death sentence. So I told no one.

One person knew. Stacey, my best friend since third grade, across-the-street neighbor, secret-keeper, fellow Girl Scout, asked me one day before the bell rang in the school commons if my dad was gay. She had found out from her little sister, my little sister’s best friend. I froze in terror. Avoided eye contact. Stared down at her Robert Plant t-shirt instead. The psychedelic swirls of celtic knots made me feel ashamed that I didn’t know who Robert Plant was, and that my parents were getting a divorce, and that my dad was gay. Stacey had always been cooler than me. How could I tell her? But how could I not? I finally managed a small head nod. Begged her not to tell anyone. I didn’t need to beg - she wouldn’t dream of telling.

Eventually, though, I did tell two more people. Anna and Amy, the other “unacceptables” on our block. Anna was Mormon, like me, but her dad didn’t attend church. Amy’s parents, also Mormon, had been the first out of the gang to get divorced. Stacey was methodist. Worse than an atheist, according to the Church.

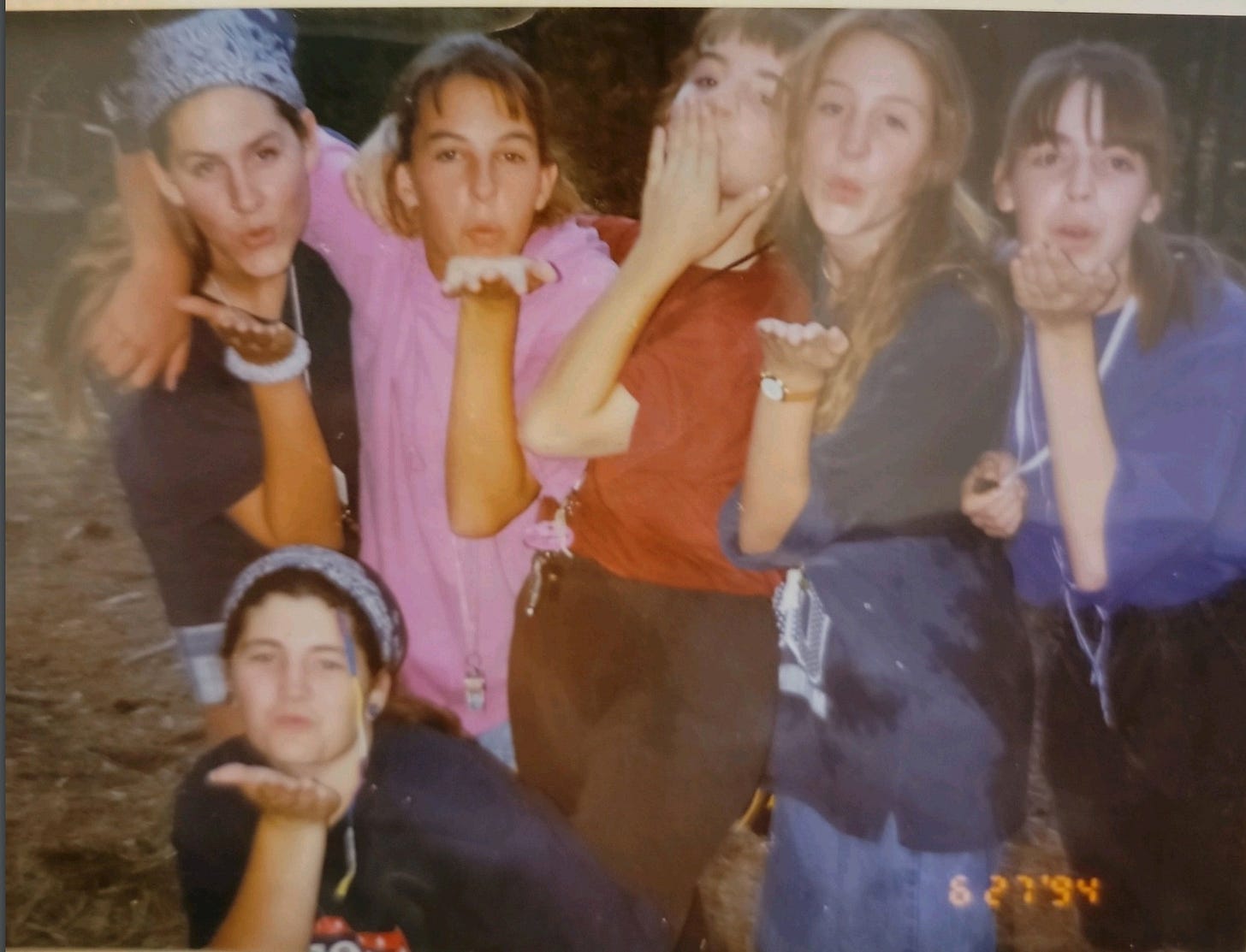

We tore up the summer streets east of Oakland, California in all the best, innocent ways that early teen, semi-religious girls can. Our own little rat pack. The Raisin Girls. Making fun of the Cornflake Girls who waltzed around school with full make-up and sticks in their butts. Those girls had new clothes and lived in houses with four detached walls and private backyards. Swimming pools. Bedrooms they didn’t share with siblings. Cable TV.

Our neighborhood was the real deal. Life as it should be. We lived in duplexes, on the north side of the train tracks that ran along the end of our street, walking distance to K-Mart and McDonald’s. We might not have had it like those girls; at least we weren’t like those other girls. The ones on the south side of the train tracks; or the ones who lived one block to the east - in apartments. We wore second-hand clothes, but at least we had clothes. Our poverty was not as bad as theirs. It was the perfect amount of poverty to stay relevant.

So there we were, fourteen years old. Budding girls at different stages of development, happily planted in the middle of 1990’s working-class west coast. Anna and Amy already had full racks, Stacey at an A cup. They forgave me for stuffing. We walked to school together along the train tracks and ran around barefoot on hot nights. Sleepovers included ouija boards and confessions about crushes. Stacey’s big crush was Anthony Kiedis; I preferred Axel Rose. We had all kissed a boy, but stopped at second base, in between chaste and whore. Double-dating at dances, sharing homework, playing in band together, we were movie-perfect teenage besties. (Flashback to dancing with Rory Griffin to November Rain at a high school dance. We knew all the words - slow dancing and then head thrashing at all the appropriate parts.)

One summer night, we were walking home from the mall, high on the warm air after a 98-degree day, and drunk on the joy of being around those boys at the mall. We walked arm-in-arm, a friendship wall, down the sidewalk. Giggling and whispering like only girls can. Then, out of nowhere, a white van pulled up next to us. I heard somewhere that almost every Gen X-er has a story of a kidnapping, or near-kidnapping. This is mine, or, ours.

The van door slid open to reveal a man. Dressed only in a giant diaper. Really. Girl scout’s honor.

And what was our reaction to such a dangerous spectacle? Did we spray him with mace or get on our phones or scream in panic? No. We laughed. Hilariously and genuinely. Laughter that rolled through the thick California night air. We leaned on each other in pure glee and would have literally ‘laughed our assess off’ if that phrase had been invented. Tears of mirth streamed down our faces. The last thing we saw was a flustered and embarrassed would-be abductor shamefully close the door to his van and drive off. Our laughter echoed all the way down the streets to our block and through the years afterward.

That was Freshman year. One girl in our year got pregnant. Joe, next door, got arrested after a fight in the cafeteria. We took both events in stride. Isn’t that part of growing up? We’re all just one mistake away from a different life. Pearl Jam hit the scene. Kurt Cobain killed himself. Clinton pissed off a lot of people. And four girls had a temporary, magical, moment of true friendship.

Amy’s dad moved out of the house around the corner, she went to a different school. Anna went goth. Stacey went full-on band geek. I moved to Washington. Then Colorado. Stacey and I wrote letters. Like, real letters, with paper and stamps. Later, we emailed and friended each other on Facebook.

Life is funny sometimes. Not funny, haha, but funny in a way that if you don’t laugh you’ll cry. You either find it funny or you go crazy. We made it out of that ghetto-neighborhood-that-wasn’t-a-ghetto-neighborhood. We’re all in our mid-forties now, with rich, full lives. At least, we’re supposed to be. Stacey married young and had two kids right away. Her son is about to start college. Her husband reminds me of her father - kind eyes and a long beard. I don’t know what happened to Amy.

Anna didn’t make it out. At twenty-five, her boyfriend, and the father of her toddler, killed her and then killed himself. The reality of our childhood punched me in the face when Stacey called to tell me. I had been back to visit not too long before. Our old neighborhood hadn’t aged well. Meth houses, condemned buildings, rusted-out cars in the yards, and homelessness on the corners. I saw Anna. She was as irreverent and fun as she ever was. She had left the church, like me. We joked about how ridiculous it all was.

I think about her from time to time, about how old her daughter would be.

Ours was not an apathy born from not caring, but from being faced with the reality of the world. We didn’t sugar-coat things. Our dads were useless, our moms unavailable. The world was coming together, but also falling apart. Rodney King caused a ripple of racially-charged riots up and down the west coast, decades before anyone had heard George Floyd’s name. America saw an unprecedented decrease in overall violent crime, while gun shots sounded on our block at night and we held school-shooting drills in junior high. Princess Diana was our savior and George Bush, Sr. was the enemy. Jon Bon Jovi was our knight on a steel horse. The Wall may have come down, but the oceans were heating up. Whitney Houston told us we were the future. R.E.M. said it was the end of the world.

What do you do when the pain of life becomes unbearable? You laugh.

Ha! I made it to fame! It was always fun dancing with you, and it was always fun being your friend!